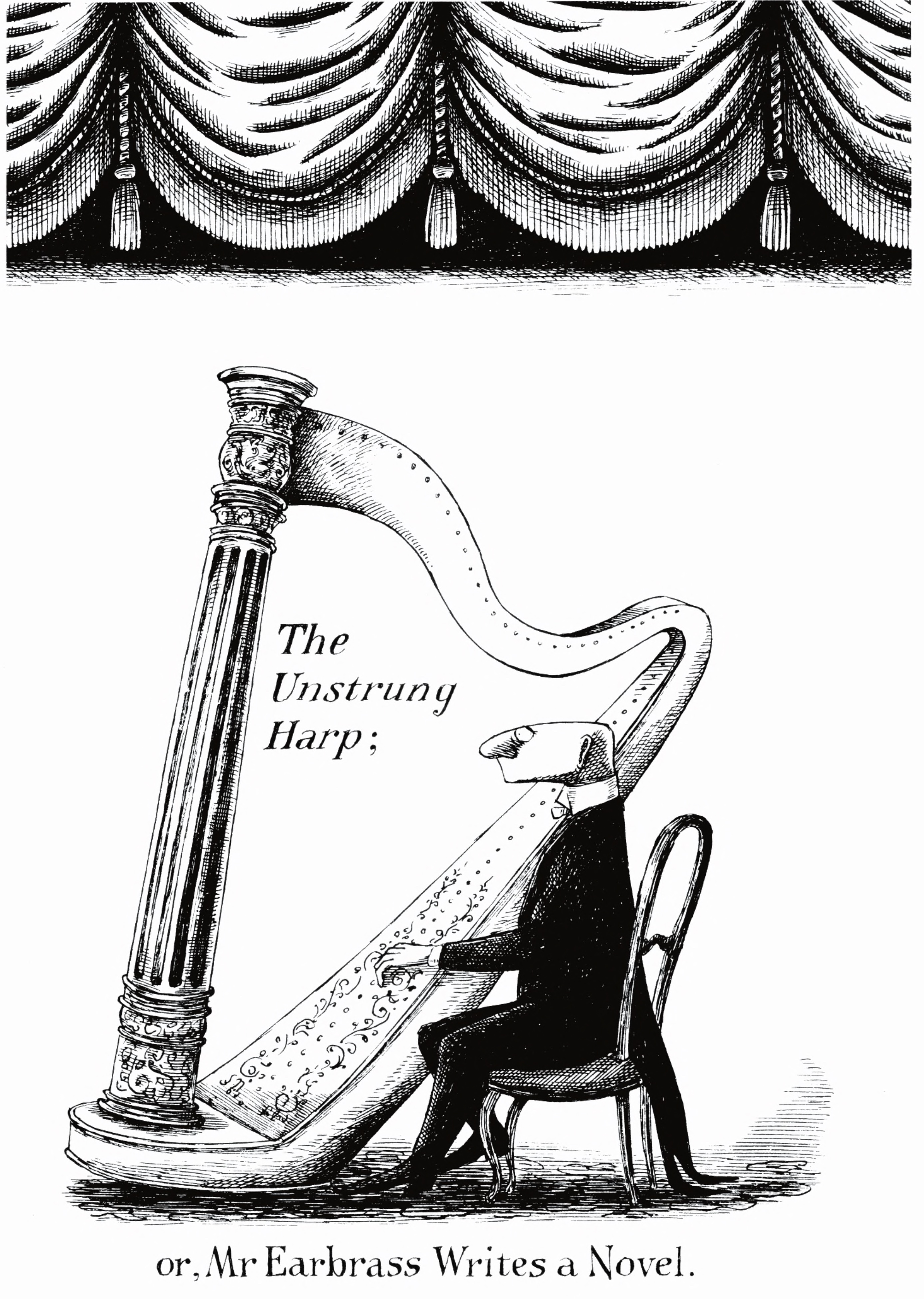

Edward Gorey - The Unstrung Harp (full 50MB version)

(c) Edward Gorey, retrieved from archive.org . To imporove readability, keep the text moving up and down within the pictures.

Mr C(lavius) F(rederick) Earbrass is, of

course, the well-known novelist. Of his books,

"A Moral Dustbin", "More Chains Than Clank",

"Was it Likely?", and the Hipdeep trilogy are,

perhaps, the most admired. Mr Earbrass is

seen on the croquet lawn of his home,

Hobbies Odd, near Collapsed Pudding in

Mortshire. He is studying a game left

unfinished at the end of summer.

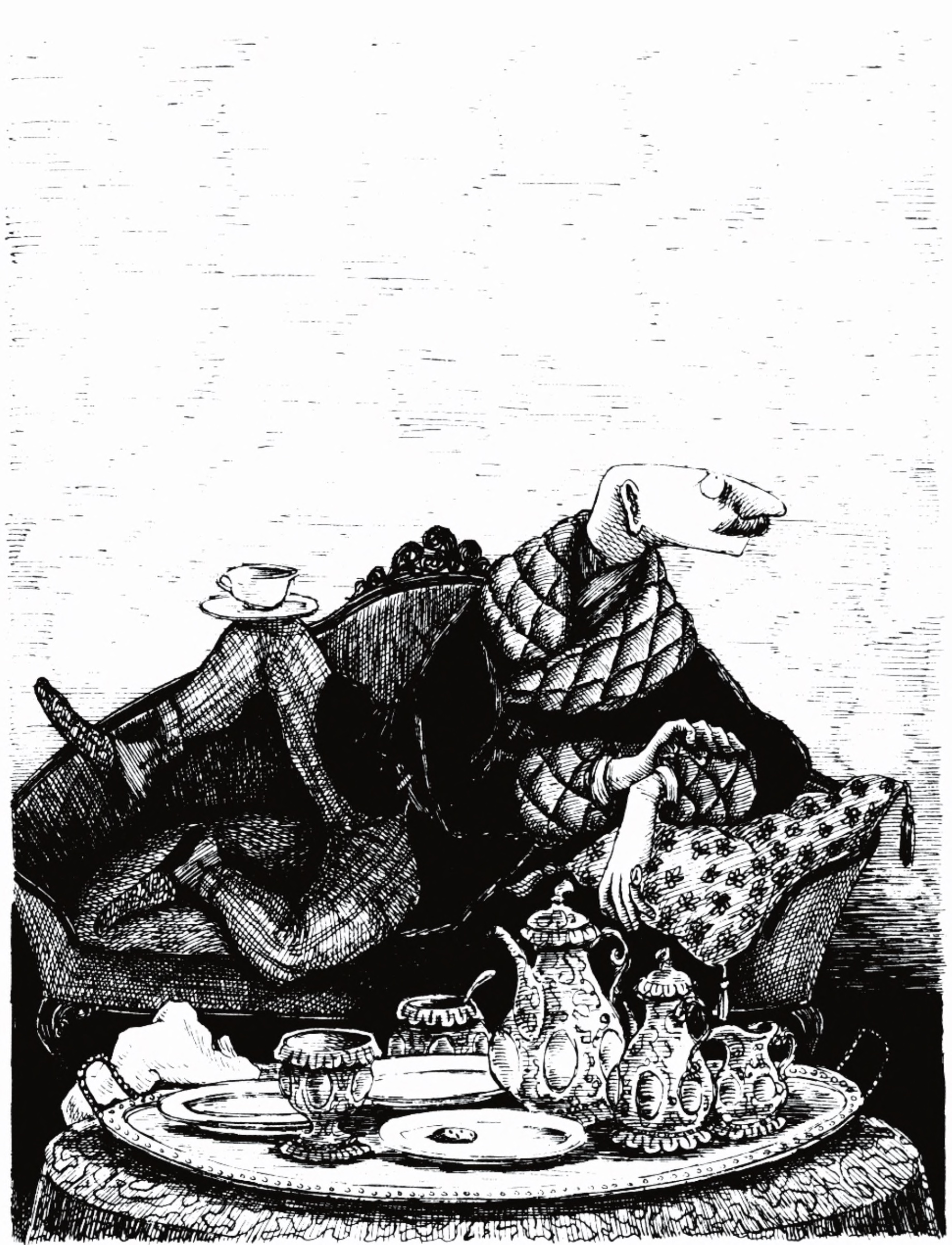

On November 18th ...

... biscuit on the plate.

On November 18th of alternate years

Mr Earbrass begins writing ‘his new novel’.

Weeks ago he chose its title at random from

a list of them he keeps in a little green

note book. It being tea-time of the 17th,

he is alarmed not to have thought of a plot

to which The Unstrung Harp might apply,

but his mind will keep reverting to the

last biscuit on the plate.

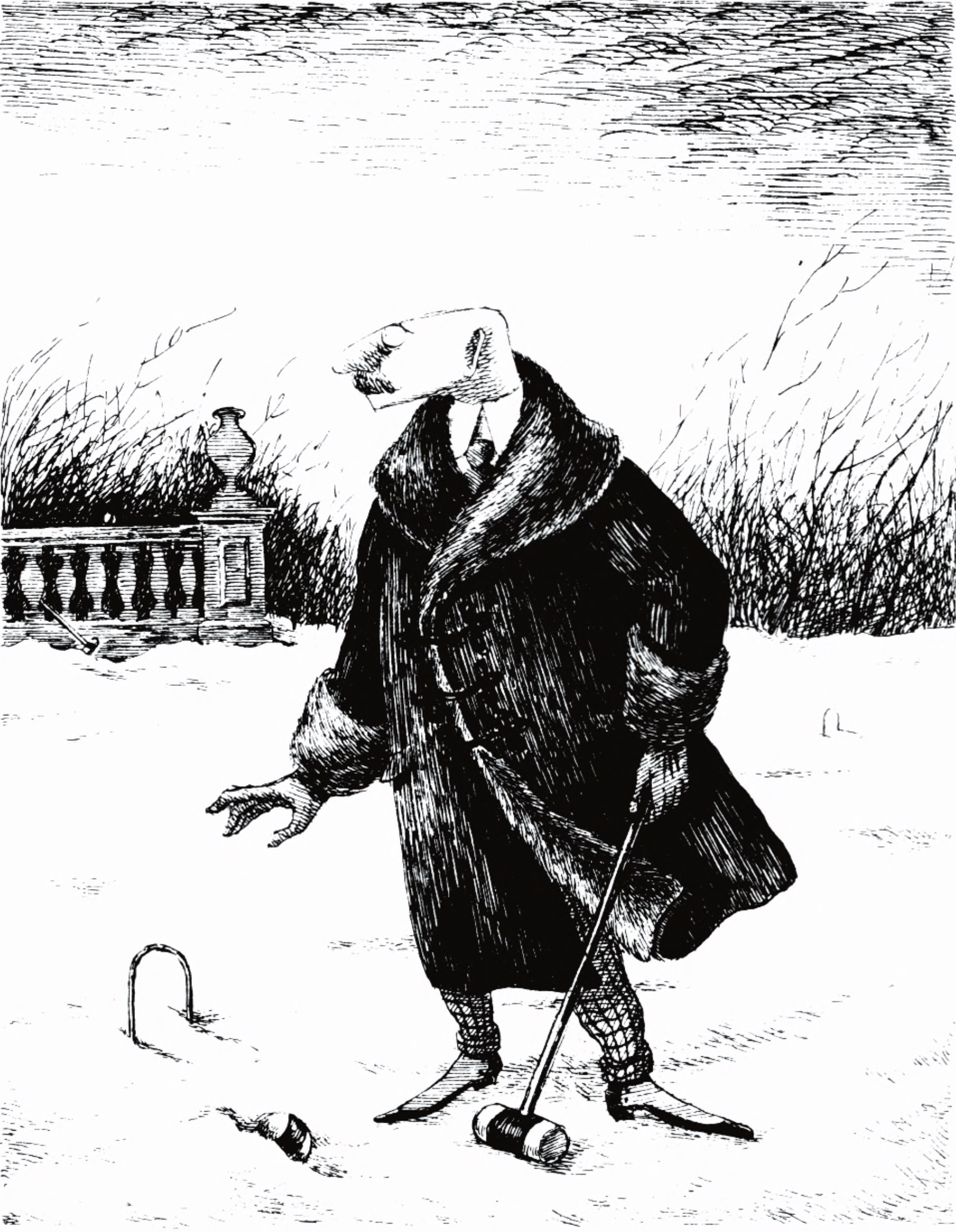

Snow was falling ...

... worn hind-side-to.

Snow was falling when Mr Earbrass

woke, which suggested he open TUH with

the first flakes of what could be developed

into a prolonged and powerfully purple

blizzard. On paper, if not outdoors, they

have kept coming down all afternoon,

over and over again, in all possible ways;

and only now, at nightfall, have done so

satisfactorily. For writing Mr Earbrass

affects an athletic sweater of forgotten

origin and unknown significance; it is

always worn hind-side-to.

Several weeks later ...

... dragged or not.

Several weeks later, the loofah trickling

on his knees, Mr Earbrass mulls over an

awkward retrospective bit that ought to

go in Chapter II. But where? Even the

voice of the omniscient author can

hardly afford to interject a seemingly

pointless anecdote concerning Ladderback

in Tibet when the other characters are

feverishly engaged in wondering whether

to have the pond at Disshiver Cottage

dragged or not.

Mr Earbrass belongs ...

... the Poddington Te Deum.

Mr Earbrass belongs to the straying, rather

than to the sedentary, type of author. He is

never to be found at his desk unless actually

writing down a sentence. Before this

happens he broods over it indefinitely

while picking up and putting down again

small, loose objects; walking diagonally

across rooms ; staring out windows ;and so

forth. He frequently hums, more in his

mind than anywhere else, themes from

the Poddington Te Deum..

It was one of Mr Earbrass’s ...

... better ideas.

It was one of Mr Earbrass’s better days; he

wrote for so long and with such intensity that

when he stopped he felt quite sick. Having

leaned out a window into a strong wind for

several minutes, he is now restoring himself

in the kitchen and rereading TUH as far as he

has gotten. He cannot help but feel that

Lirp's return and almost immediate impalement

on the bottle tree was one of his better ideas.

The jelly in his sandwich is about to get all

over his fingers.

The jelly in his sandwich ...

... over his fingers.

Mr Earbrass has finished ...

... no other character capable of them.

Mr Earbrass has finished Chapter VII, and

it is obvious that before plunging ahead

himself he has got to decide where the plot

is to go and what will happen to it on

arrival. He is engaged in making diagrams

of possible routes and destinations, and

wishing he had not dealt so summarily with

Lirp, who would have been useful for taking

retributive measures at the end of Part Three.

At the moment there is no other character

capable of them.

Out for a short drive ...

... TUB shifts to Hangdog Hall.

Out for a short drive before a supper of

oysters and trifle, Mr Earbrass stops near

the abandoned fireworks factory outside

Something Awful. There is a drowned sort of

yellow light in the west, and the impression

of desolation and melancholy is remarkable.

Mr Earbrass jots down a few visual notes

he suspects may be useful when he reaches

the point where the action of TUB shifts to

Hangdog Hall.

Mr Earbrass was virtually ...

... their authorship.

Mr Earbrass was virtually asleep when

several lines of verse passed through his

mind and left it hopelessly awake. Here

was the perfect epigraph for TUH:

A horrid ?monster has been [something]

delay’d

By your/their indiff’rence in the dank

brown shade

Below the garden...

His mind’s eye sees them quoted on the

bottom third of a right-hand page in a

(possibly)olive bound book he read at least

five years ago. When he does find them, it

will be a great nuisance if no clue is given

to their authorship.

Mr Earbrass has driven ...

... Angus?

Mr Earbrass has driven over to Nether

Millstone in search of forced greengages,

but has been distracted by a bookseller’s.

Rummaging among mostly religious tracts

and privately printed reminiscences, he

has come across The Meaning of the Mouse,

his second novel. In making sure it has

not got there by mistake (as he would

hardly care to pay more for it), he

discovers it is a presentation copy. For

Angus— will you ever forget the bloaters?

Bloaters? Angus?

The first draft of TUH ...

... vanish.

The first draft of TUH is more than half

finished, and for some weeks its characters

have been assuming a fitful and cloudy

reality. Now a minor one named Glassglue

has materialized at the head of the stairs

as his creator is about to go down to dinner.

Mr Earbrass was aware of the peculiarly

unpleasant nubs on his greatcoat, but not the

blue-tinted spectacles. Glassglue is about to

mutter something in a tone too low to be

caught and, stepping sideways, vanish.

Mr Earbrass has been ...

... room on the third floor?

Mr Earbrass has been rashly skimming

through the early chapters. which he has not

looked at for months, and now sees TUH for

what it is. Dreadful, dreadful, DREADFUL. He

must be mad to go on enduring the unexquisite

agony of writing when it all turns out drivel.

Mad. Why didn’t he become a spy? How does

one become one? He will burn the MS. Why

is there no fire? Why aren’t there the

makings of one? How did he get in the

unused room on the third floor?

Mr Earbrass returned ...

... deprived of novels.

Mr Earbrass returned from a walk to find

a large carton blocking the hall. Masses of

brow paper and then tissue have reluctantly

given up an unnerving silver gilt combination

epergne and candelabrum. Mr Earbrass

recollects a letter from a hitherto unknown

admirer of his work, received the week before;

it hinted at the early arrival of an offering

that embodied, in a different but kindred

form, the same high-souled aspiration that

animated its recipient’s books. Mr Earbrass

can only conclude that the apathy of the

lower figures is due to their having been

deprived of novels.

Even more harrowing ...

... twining up his ankles.

Even more harrowing than the first chapters

of a novel are the last, for Mr Earbrass anyway.

The characters have one and all become

thoroughly tiresome, as though he had been

trapped at the same party with them since

the day before; neglected sections of the plot

loom on every hand, waiting to be disposed of;

his verbs seem to have withered away and

his adjectives to be proliferating past control.

Furthermore, at this stage he inevitably gets

insomnia. Even rereading The Truffle Plantation

(his first novel) does not induce sleep. In the

blue horror of dawn the vines in the carpet

appear likely to begin twining up his ankles.

Though TUH is within ...

... out of his mind.

Though TUH is within less than a chapter

of completion, Mr Earbrass has felt it his

cultural and civic duty, and a source of

possible edification, to attend a performance

at Lying-in-the-Way of Prawne’s The Nephew's

Tragedy. It is being put on, for the first

time since the early seventeenth century,

by the West Mortshire Impassioned Amateurs

of Melpomene. Unfortunately, Mr Earbrass

is unable to take in even one of its five

plots because he cannot get those few

unwritten pages out of his mind.

In that brief moment ...

... belonged to someone else.

In that brief moment between day and

night when everything seems to have stopped

forgoodandall, Mr Earbrass has written the

last sentence of TUH. The room’s appearance

of tidiness and Mr Earbrass's of calm are

alike deceptive. The MS is stuffed all

anyhow in the lower right hand drawer of

the desk and Mr Earbrass himself is wildly

distrait. His feet went to sleep some time ago,

there is a dull throbbing behind his left ear,

and his moustache feels as uncomfortable as if

it were false, or belonged to someone else.

The next day ...

... more helpful.

The next day Mr Earbrass is conscious but

very little more. He wanders through the house,

leaving doors open and empty tea cups on the

floor. From time to time the thought occurs

to him that he really ought to go and dress,

and he gets up several minutes later, only to

sit down again in the first chair he comes

to. The better part of a week will have elapsed

before he has recovered enough to do anything

more helpful.

Some weeks later ...

... its original state.

Some weeks later, with pen, ink, scissors,

paste, a decanter of sherry, and a vast

reluctance, Mr Earbrass begins to revise TUH.

This means, first, transposing passages,

or reversing the order of their paragraphs, or

crumpling them up furiously and throwing

them in the waste-basket. After that there

is rewriting. This is worse than merely

writing, because not only does he have to

think up new things just the same, but at

the same time try not to remember the old

ones. Before Mr Earbrass is through, at

least one third of TUH will bear no

resemblance to its original state.

Mr Earbrass sits ...

... loathsome proceeding.

Mr Earbrass sits on the opposite side of the

study from his desk, gathering courage for

the worst part of all in the undertaking of a

novel, i.e., making a clean copy of the final

version of the MS. Not only is it repulsive to

the eye and hand, with its tattered edges. stains,

rumpled patches, scratchings-out, and scribblings,

but its contents are, by this time, boring to

the point of madness. A freshly-filled inkwell,

new pheasant-feather pens, and two reams of

the most expensive cream laid paper are

negligible inducements for embarking on

such a loathsome proceeding.

Holding TUH ...

... a good deal of fuss.

Holding TUH not very neatly done up in

pink butcher’s paper, which was all he could

find in a last-minute search before leaving

to catch his train for London, Mr Earbrass

arrives at the offices of his publishers to

deliver it. The stairs look oddly menacing,

as though he might break a leg on one of them.

Suddenly the whole thing strikes him as very

silly, and he thinks he will go and drop his

parcel off the Embankment and thus save

everyone concerned a good deal of fuss.

Mr Earbrass escaped ...

... put under a glass bell.

Mr Earbrass escaped from Messrs Scuffle

and Dustcough, who were most anxious to go

into all the ramifications of a scheme for

having his novels translated into Urdu, and

went to call on a distant cousin. The latter

was planning to do the antique shops this

afternoon, so Mr Earbrass agreed to join him.

In the eighteenth shop they have visited,

the cousin thinks he sees a rare sort of

lustre jug, and Mr Earbrass irritatedly

wonders why anyone should have had a

fantod stuffed and put under a glass bell.

The night before ...

... the literary life.

The night before returning home to

Mortshire Mr Earbrass allows himself to be

taken to a literary dinner in a private dining

room of Le Trottoir Imbécile . Among his fellow-

authors, few of whom he recognizes and none

of whom he knows, are Lawk, Sangwidge,

Ha’p’orth, Avuncular, and Lord Legbail. The

unwell-looking gentleman wrapped in a

greatcoat is an obscure essayist named

Frowst. The talk deals with disappointing

sales, inadequate publicity, worse than

inadequate royalties, idiotic or criminal

reviews, others’ declining talent, and the

unspeakable horror of the literary life.

TUH is over ...

... pecuniary limits.

TUH is over so to speak, but far from done

with. The galleys have arrived, and Mr

Earbrass goes over them with mingled

excitement and disgust. It all looks so

different set up in type that at first he

thought they had sent him the wrong ones

by mistake. He is quite giddy from trying

to physically control the sheets and at

the same time keep the amount of

absolutely necessary changes within the

allowed pecuniary limits.

Mr Earbrass has received ...

... Scuffle and Dustcough.

Mr Earbrass has received the sketch for the

dust-wrapper of TUH. Even after staring at

it continuously for twenty minutes, he

really cannot believe it. Whatever were

they thinking of? That drawing. Those

colours. Ugh. On any book it would be

ugly, vulgar, and illegible . On his book it

would be these, and also disastrously

wrong. Mr Earbrass looks forward to an

exhilarating hour of conveying these

sentiments to Scuffle and Dustcough.

Things contined ...

... his next book.

Things contined to come, this time Mr

Earbrass’s six free copies of TUH. There are,

alas, at least three times that number of

people who expect to receive one of them.

Buying the requisite number of additional

copies does not happen to be the solution, as it

would come out almost at once, and everyone

would be very angry at his wanton distribution

of them to just anyone, and write him little

notes of thanks ending with the remark that

TUH seems rather down from your usual level

of polish but then you were probably in a

hurry for the money. If it didn’t come out,

the list would be three times larger for

his next book.

To day TUH is published ...

... and pointless embarrassment.

To day TUH is published, and Mr Earbrass

has come into Nether Millstone to do some

errands which could not be put off any longer.

He has been uncharacteristically thorough

about doing them, and it is late afternoon

before he pauses in front of a bookseller’s

window on the way back to his car. Having

made certain, out of the corner of his eye,

a copy of TUH was in it, he is carefully

reading the title of every other book there

in a state of extreme and pointless embarrassment.

Scuffle and Dustcough have ...

... on page 33.

Scuffle and Dustcough have thoughtfully,

if gratuitously, sent all the papers with

reviews in them. They make a gratifyingly

large heap. Mr Earbrass refuses to be

intimidated into rushing through them, but

he is having a certain amount of difficulty in

concentrating on, or, rather, making any sense

whatever out of, A Compendium of the Minor

Heresies of the Twelfth Century in Asia Minor.

He has been meaning to finish it ever

since he began it two years and seven

months before, at which time he bogged

down on page 33.

At an afternoon ...

... very weak indeed.

At an afternoon forgathering at the

Vicarage vaguely in Mr Earbrass’s honor,

where he has been busy handing round cups

of tea, he is brought up short by Col Knout,

M.F.H. of the Blathering Hunt. He demands

to know just what Mr Earbrass was ‘getting

at’ in the last scene of Chapter XIV. Mr

Earbrass is afraid he doesn’t know what

the Colonel is. Is what? Getting at himself.

The Colonel snorts, Mr Earbrass sighs.

This encounter, which will go on for some

time and get nowhere, will leave Mr

Earbrass feeling very weak indeed.

Mr Earbrass stands ...

... mourning elsewards.

Mr Earbrass stands on the terrace at

twilight. It is bleak; it is cold; and the

virtue has gone out of everything. Words

drift through his mind: anguish turnips

conjunctions illness defeat string

parties no parties urns desuetude

disaffection claws loss Trebizond

napkins shame stones distance fever

Antipodes mush glaciers incoherence

labels miasma amputation tides

deceit mourning elsewards ...

Before he knew ...

... he is on the other side.

Before he knew what he was doing, Mr

Earbrass found he had every intention of

spending a few weeks on the Continent. In

a trance of efficiency, which could have

surprised no one more than himself, he

made the complicated and maddening

preparations for his departure in no time

at all. Now, at dawn, he stands, quite numb

with cold and trepidation, looking at the

churning surface of the Channel. He

assumes he will be horribly sick for hours and

hours, but it doesn’t matter. Though he is a

person to whom things do not happen,

perhaps they may when he is on the other side.